Concept

About this project

Beethoven was my catalyst rebridging my relationship to the piano after lapsing nearly twenty years. I had read his “Heiligenstadt Testament” and it brought back painfully the moment in my late 20s when I realized I had no hearing remaining in my right ear. It felt like a physical blow, a punch to the stomach. I was down half of what little hearing I was born with—residual 22% of normal sound perception range in both ears. Not to compare myself to the level of Beethoven’s genius, but the visceral feeling of having lost a part of how one perceives one’s world is a universal one.

My relationship with the piano started when I was 6, when a rather forbidding-looking lady wearing a proper black dress suit, peter pan collars, and all-white hair in a prim bun came into my first grade class and explained that she was a piano teacher. I was just fitted with two hearing aids when public health tests revealed I was hard of hearing. But with the aids I was functional in a regular class. As with most Asian families, some kind of extra-curricular activity was much encouraged; it was never too early to start creating a “well-rounded” college application, even in first grade.

It wasn’t love at first lesson. Like any kid I hated to practice, which of course drove my teacher and my mother crazy. To fool my mom, I used to park a book on the piano to read while mindlessly repeating a random phrase from my piece, ad nauseum by finger memory. Upon finishing a page of the book, I’d pick the next random phrase for my fingers, just to create the illusion of actually progressing through a piece. It didn’t work for long —the automaton banging was too suspicious to pass for practice, and my mom caught me out soon enough. Needless to say, my book got confiscated. The non-music one, that is.

Over time, music appreciation flourished and became more structured as I was accepted into the preparatory department of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. I no longer sneaked books to my practice; practice came naturally. It became a conversation. I may have trouble understanding speech, but with music I could follow the ebb and tide of its emotional narrative. There was so much more than organized sound — texture, color, and I saw and felt the wrong notes I played with my fingertips if I could not hear them.

Cochlear implant

When I was in my late 20s what remaining hearing I had in my right ear disappeared; I thought my hearing aid had merely died, but testing showed that there was no perception of sound for any aid to amplify. Fast forward 15 years, I was approved for cochlear implant insurance coverage, and I received the surgery a month after finishing my MFA program, on June 6 (but thankfully not at 6 o’clock, or it would have come too uncomfortably close to the number 666). The timing felt like a turning point. During my graduate studies I had begun my work connecting my hearing/not hearing with my visual art. I knew that a my receiving a cochlear implant would not be a light switch flicking on instant hearing; because the nerves in my deaf ear have been non-functional for so many years it would be more work for the brain to make sense of data coming in from a disused channel. Nevertheless it felt right for me to resume my piano studies again. I reconnected with my piano teacher from my preparatory days at the SF Conservatory and dusted off my piano.

Reconciling with playing the piano and a million ways to (mis)hear it

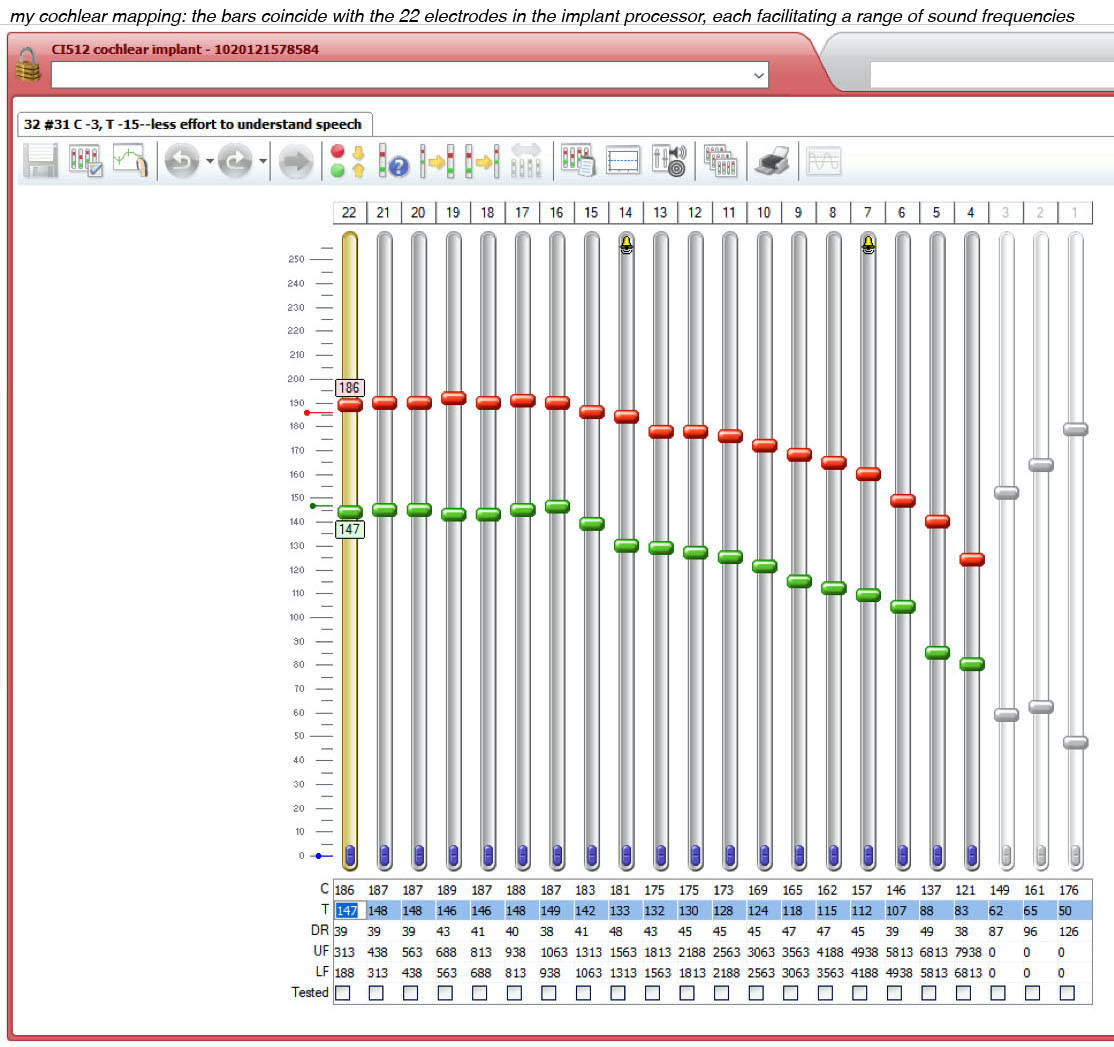

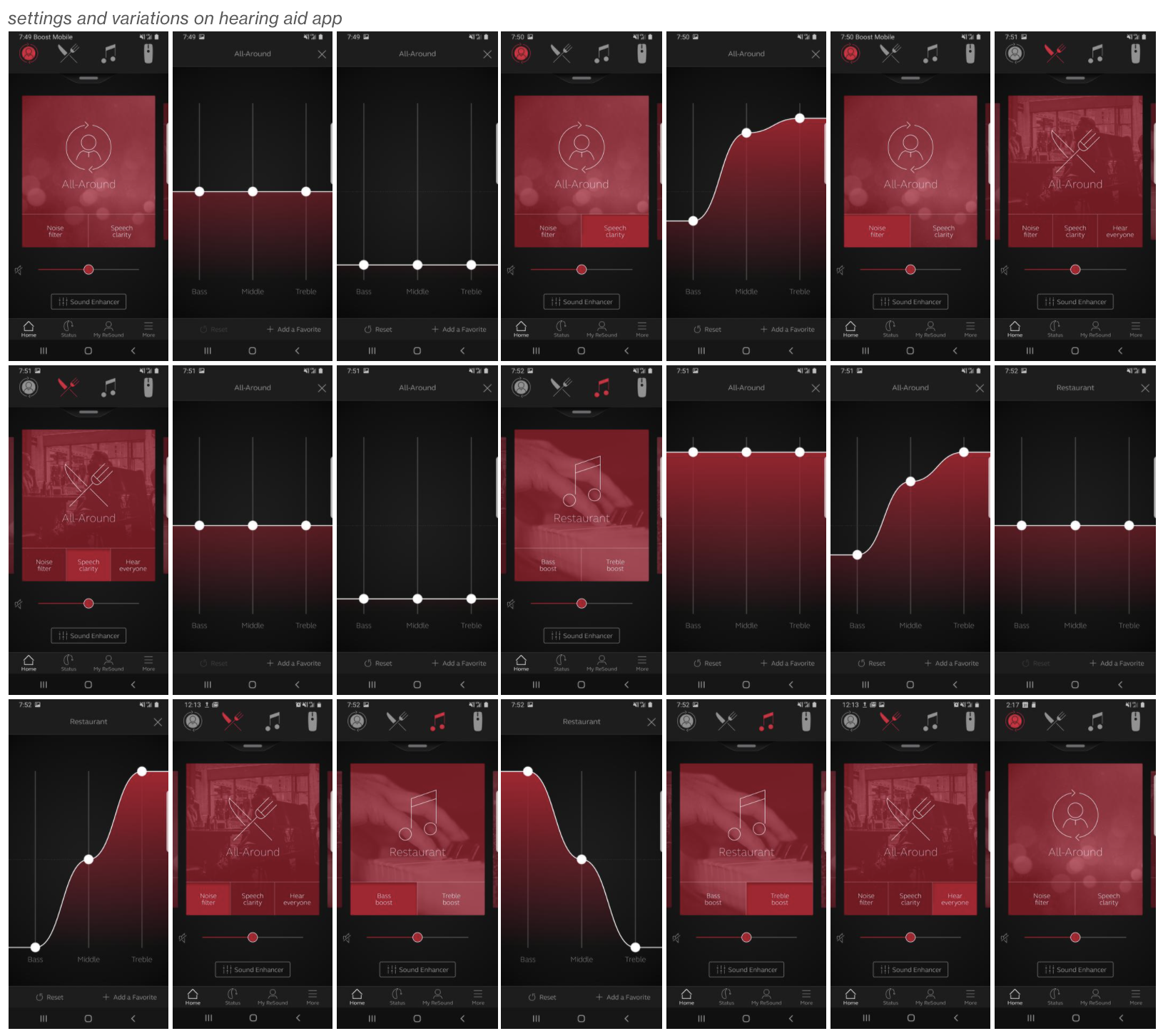

Turns out I have to dust off more than my piano. My fingers have lost the stamina and some of the dexterity. I had to learn to practice efficiently again. Playing for anyone other than an empty room was a mindtrap; as soon as someone as much as walked by I would be distracted and completely lose it. And the sound — crafting the quality and texture of sound that I remembered is something of a guesstimate. Initially my piano teacher had to help me balance the volume between my right and left hands. Given that the bass creates greater vibrations, I would tend to favor the bass, but that’s usually not where the melody is. She also told me I needed get my lead foot off the damper pedal; for me wallowing in the vibrations was soothing, but it sounded terrible. Different available settings on my hearing aid (3 programs and various adjustments) + cochlear implant (2 programs) added up to overwhelming potential combinations. After a few months of testing out the seemingly infinite possibilities, I’ve narrowed them down to 2 or 3 settings. I have yet to think of a way not to appear rude fiddling around on my phone hearing app while people stand around waiting for me to bring their voice into focus. But now with everything going Zoom, I had a few more sound wrenches thrown in to experiment with. With technology, my audial reality is ever-changing, having to contend with unforseen layers of sound interpretations.

![]()

![]()

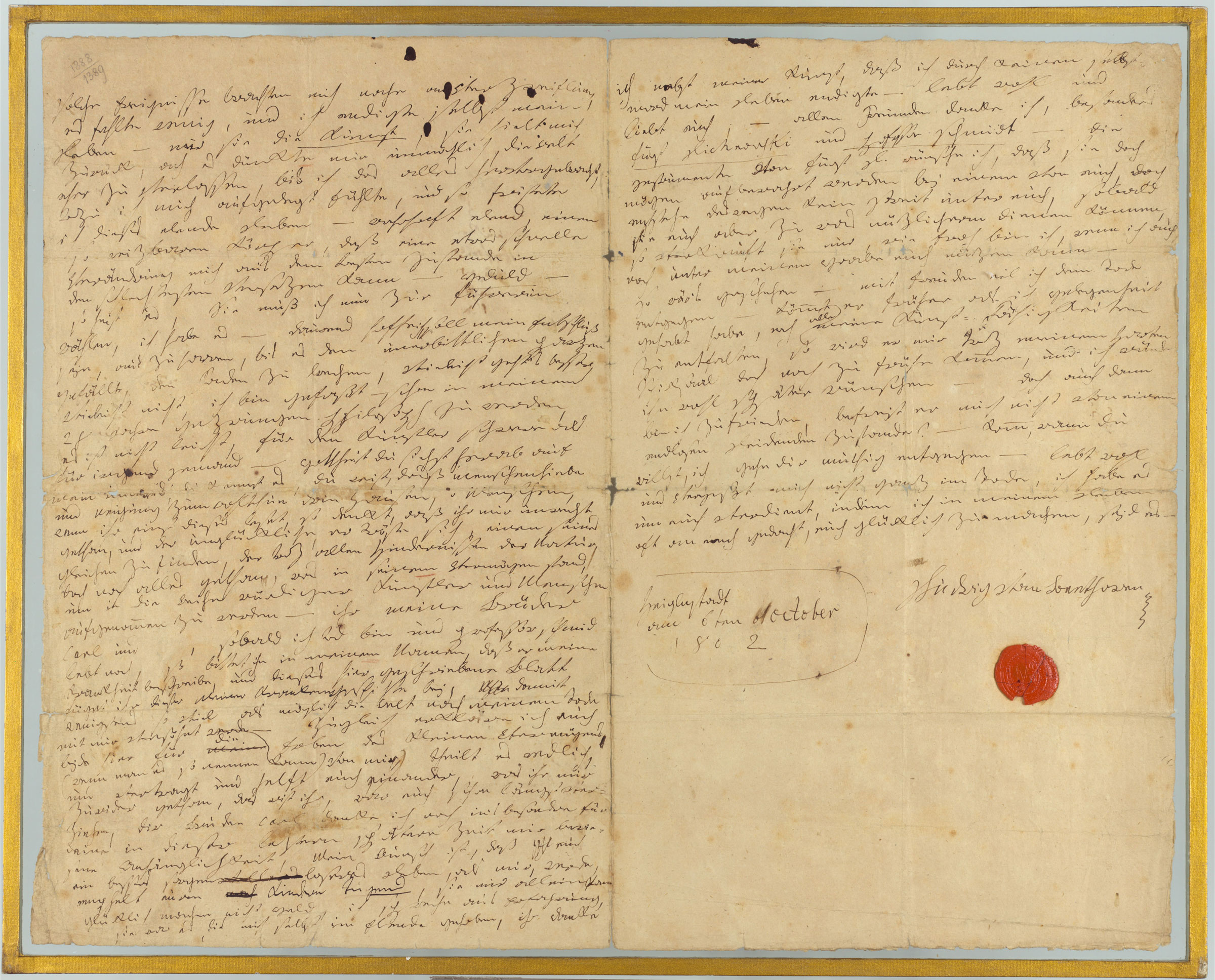

While I have the option of modern technology to fill in my hearing black hole, Beethoven had none, in his time. He went through a revolving door of physicians — not only for his hearing, but also for other body ailments. Many prescribed treatments that would be eyebrow-raising today, but such was the state of medical science at the cusp of 19th century. In his “Heiligenstadt Testament” Beethoven wrote that he had considered ending this life, but

Multisensorial hearing (and listening)

I looked to Beethoven thinking about how we deaf (or mostly deaf) people access sound multi-sensorially—through sight, touch, vibration, patterns. Sound takes on a physical presence, whereas in reality it's an incorporeal phenomenon. And, like Beethoven, I had an experience of hearing, one that was achieved with hearing aids, but it was natural hearing, so it has a particular texture, timbre, and quality that holds in my memory. Like all artists, I think one has to see, or hear, something internally to begin crafting a piece. Imagination has to start from a memory.

Beethoven’s imagination of sound did not stop at his ears. True to his ever-experimental spirit pushing the boundaries of his musical compositions and the physical possibilities of the piano, he also strove to experience sound through other senses of his body. In the film “Immortal Beloved” actor Gary Oldman offered an interpretation of Beethoven playing the first movment of the Moonlight Sonata with his ear on the piano to feel the vibrations. Records from his conversation book revealed that he was in communication with physicist and acoustician Ernst Chladni who discovered that pitches of different frequencies created unique geometric patterns in sand on a plate. Could he have been trying to “see” sound?

The human body always strives to make sense of the environment it exists in. Where one channel is blocked, it adapts and delegates awareness to the network of other senses. As I relearn the Appassionata Sonata (published a year after the Heiligenstadt Testament) with my cochlear implant, I can only pay homage to Beethoven’s tenacity and determination, and his will to forge his own reality.

My relationship with the piano started when I was 6, when a rather forbidding-looking lady wearing a proper black dress suit, peter pan collars, and all-white hair in a prim bun came into my first grade class and explained that she was a piano teacher. I was just fitted with two hearing aids when public health tests revealed I was hard of hearing. But with the aids I was functional in a regular class. As with most Asian families, some kind of extra-curricular activity was much encouraged; it was never too early to start creating a “well-rounded” college application, even in first grade.

It wasn’t love at first lesson. Like any kid I hated to practice, which of course drove my teacher and my mother crazy. To fool my mom, I used to park a book on the piano to read while mindlessly repeating a random phrase from my piece, ad nauseum by finger memory. Upon finishing a page of the book, I’d pick the next random phrase for my fingers, just to create the illusion of actually progressing through a piece. It didn’t work for long —the automaton banging was too suspicious to pass for practice, and my mom caught me out soon enough. Needless to say, my book got confiscated. The non-music one, that is.

Over time, music appreciation flourished and became more structured as I was accepted into the preparatory department of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. I no longer sneaked books to my practice; practice came naturally. It became a conversation. I may have trouble understanding speech, but with music I could follow the ebb and tide of its emotional narrative. There was so much more than organized sound — texture, color, and I saw and felt the wrong notes I played with my fingertips if I could not hear them.

Cochlear implant

When I was in my late 20s what remaining hearing I had in my right ear disappeared; I thought my hearing aid had merely died, but testing showed that there was no perception of sound for any aid to amplify. Fast forward 15 years, I was approved for cochlear implant insurance coverage, and I received the surgery a month after finishing my MFA program, on June 6 (but thankfully not at 6 o’clock, or it would have come too uncomfortably close to the number 666). The timing felt like a turning point. During my graduate studies I had begun my work connecting my hearing/not hearing with my visual art. I knew that a my receiving a cochlear implant would not be a light switch flicking on instant hearing; because the nerves in my deaf ear have been non-functional for so many years it would be more work for the brain to make sense of data coming in from a disused channel. Nevertheless it felt right for me to resume my piano studies again. I reconnected with my piano teacher from my preparatory days at the SF Conservatory and dusted off my piano.

Reconciling with playing the piano and a million ways to (mis)hear it

Turns out I have to dust off more than my piano. My fingers have lost the stamina and some of the dexterity. I had to learn to practice efficiently again. Playing for anyone other than an empty room was a mindtrap; as soon as someone as much as walked by I would be distracted and completely lose it. And the sound — crafting the quality and texture of sound that I remembered is something of a guesstimate. Initially my piano teacher had to help me balance the volume between my right and left hands. Given that the bass creates greater vibrations, I would tend to favor the bass, but that’s usually not where the melody is. She also told me I needed get my lead foot off the damper pedal; for me wallowing in the vibrations was soothing, but it sounded terrible. Different available settings on my hearing aid (3 programs and various adjustments) + cochlear implant (2 programs) added up to overwhelming potential combinations. After a few months of testing out the seemingly infinite possibilities, I’ve narrowed them down to 2 or 3 settings. I have yet to think of a way not to appear rude fiddling around on my phone hearing app while people stand around waiting for me to bring their voice into focus. But now with everything going Zoom, I had a few more sound wrenches thrown in to experiment with. With technology, my audial reality is ever-changing, having to contend with unforseen layers of sound interpretations.

While I have the option of modern technology to fill in my hearing black hole, Beethoven had none, in his time. He went through a revolving door of physicians — not only for his hearing, but also for other body ailments. Many prescribed treatments that would be eyebrow-raising today, but such was the state of medical science at the cusp of 19th century. In his “Heiligenstadt Testament” Beethoven wrote that he had considered ending this life, but

“Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me. So I endured this wretched existence - truly wretched for so susceptible a body, which can be thrown by a sudden change from the best condition to the very worst. - Patience, they say, is what I must now choose for my guide, and I have done so - I hope my determination will remain firm to endure until it pleases the inexorable Parcae to break the thread.”

Multisensorial hearing (and listening)

I looked to Beethoven thinking about how we deaf (or mostly deaf) people access sound multi-sensorially—through sight, touch, vibration, patterns. Sound takes on a physical presence, whereas in reality it's an incorporeal phenomenon. And, like Beethoven, I had an experience of hearing, one that was achieved with hearing aids, but it was natural hearing, so it has a particular texture, timbre, and quality that holds in my memory. Like all artists, I think one has to see, or hear, something internally to begin crafting a piece. Imagination has to start from a memory.

Beethoven’s imagination of sound did not stop at his ears. True to his ever-experimental spirit pushing the boundaries of his musical compositions and the physical possibilities of the piano, he also strove to experience sound through other senses of his body. In the film “Immortal Beloved” actor Gary Oldman offered an interpretation of Beethoven playing the first movment of the Moonlight Sonata with his ear on the piano to feel the vibrations. Records from his conversation book revealed that he was in communication with physicist and acoustician Ernst Chladni who discovered that pitches of different frequencies created unique geometric patterns in sand on a plate. Could he have been trying to “see” sound?

The human body always strives to make sense of the environment it exists in. Where one channel is blocked, it adapts and delegates awareness to the network of other senses. As I relearn the Appassionata Sonata (published a year after the Heiligenstadt Testament) with my cochlear implant, I can only pay homage to Beethoven’s tenacity and determination, and his will to forge his own reality.

Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament,

currently at the Carl von Osseitzky State and University Library

in Hamburg, Germany

currently at the Carl von Osseitzky State and University Library

in Hamburg, Germany

HEILIGENSTADT TESTAMENT

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

For my brothers Carl and [Johann] Beethoven.

Oh you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn, or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you. From childhood on, my heart and soul have been full of the tender feeling of goodwill, and I was even inclined to accomplish great things. But, think that for six years now I have been hopelessly afflicted, made worse by senseless physicians, from year to year deceived with hopes of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady (whose cure will take years or, perhaps, be impossible). Though born with a fiery, active temperament, even susceptible to the diversions of society, I was soon compelled to isolate myself, to live life alone. If at times I tried to forget all this, oh how harshly was I flung back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing. Yet it was impossible for me to say to people, "Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf." Ah, how could I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than others, a sense which I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession enjoy or ever have enjoyed. - Oh I cannot do it; therefore forgive me when you see me draw back when I would have gladly mingled with you. My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished; I can mix with society only as much as true necessity demands. If I approach near to people a hot terror seizes upon me, and I fear being exposed to the danger that my condition might be noticed. Thus it has been during the last six months which I have spent in the country. By ordering me to spare my hearing as much as possible, my intelligent doctor almost fell in with my own present frame of mind, though sometimes I ran counter to it by yielding to my desire for companionship. But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended me life - it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me. So I endured this wretched existence - truly wretched for so susceptible a body, which can be thrown by a sudden change from the best condition to the very worst. - Patience, they say, is what I must now choose for my guide, and I have done so - I hope my determination will remain firm to endure until it pleases the inexorable Parcae to break the thread. Perhaps I shall get better, perhaps not; I am ready. - Forced to become a philosopher already in my twenty-eighth year, - oh it is not easy, and for the artist much more difficult than for anyone else. - Divine One, thou seest my inmost soul thou knowest that therein dwells the love of mankind and the desire to do good. - Oh fellow men, when at some point you read this, consider then that you have done me an injustice; someone who has had misfortune man console himself to find a similar case to his, who despite all the limitations of Nature nevertheless did everything within his powers to become accepted among worthy artists and men. - You, my brothers Carl and [Johann], as soon as I am dead, if Dr. Schmid is still alive, ask him in my name to describe my malady, and attach this written documentation to his account of my illness so that so far as it possible at least the world may become reconciled to me after my death. - At the same time, I declare you two to be the heirs to my small fortune (if so it can be called); divide it fairly; bear with and help each other. What injury you have done me you know was long ago forgiven. To you, brother Carl, I give special thanks for the attachment you have shown me of late. It is my wish that you may have a better and freer life than I have had. Recommend virtue to your children; it alone, not money, can make them happy. I speak from experience; this was what upheld me in time of misery. Thanks to it and to my art, I did not end my life by suicide - Farewell and love each other - I thank all my friends, particularly Prince Lichnowsky and Professor Schmid - I would like the instruments from Prince L. to be preserved by one of you, but not to be the cause of strife between you, and as soon as they can serve you a better purpose, then sell them. How happy I shall be if can still be helpful to you in my grave - so be it. - With joy I hasten towards death. - If it comes before I have had the chance to develop all my artistic capacities, it will still be coming too soon despite my harsh fate, and I should probably wish it later - yet even so I should be happy, for would it not free me from a state of endless suffering? - Come when thou wilt, I shall meet thee bravely. - Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead; I deserve this from you, for during my lifetime I was thinking of you often and of ways to make you happy - be so -

Ludwig van Beethoven

Heiglnstadt,

October 6th, 1802

For my brothers Carl and [Johann] Beethoven.

Oh you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn, or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you. From childhood on, my heart and soul have been full of the tender feeling of goodwill, and I was even inclined to accomplish great things. But, think that for six years now I have been hopelessly afflicted, made worse by senseless physicians, from year to year deceived with hopes of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady (whose cure will take years or, perhaps, be impossible). Though born with a fiery, active temperament, even susceptible to the diversions of society, I was soon compelled to isolate myself, to live life alone. If at times I tried to forget all this, oh how harshly was I flung back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing. Yet it was impossible for me to say to people, "Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf." Ah, how could I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than others, a sense which I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession enjoy or ever have enjoyed. - Oh I cannot do it; therefore forgive me when you see me draw back when I would have gladly mingled with you. My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished; I can mix with society only as much as true necessity demands. If I approach near to people a hot terror seizes upon me, and I fear being exposed to the danger that my condition might be noticed. Thus it has been during the last six months which I have spent in the country. By ordering me to spare my hearing as much as possible, my intelligent doctor almost fell in with my own present frame of mind, though sometimes I ran counter to it by yielding to my desire for companionship. But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended me life - it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me. So I endured this wretched existence - truly wretched for so susceptible a body, which can be thrown by a sudden change from the best condition to the very worst. - Patience, they say, is what I must now choose for my guide, and I have done so - I hope my determination will remain firm to endure until it pleases the inexorable Parcae to break the thread. Perhaps I shall get better, perhaps not; I am ready. - Forced to become a philosopher already in my twenty-eighth year, - oh it is not easy, and for the artist much more difficult than for anyone else. - Divine One, thou seest my inmost soul thou knowest that therein dwells the love of mankind and the desire to do good. - Oh fellow men, when at some point you read this, consider then that you have done me an injustice; someone who has had misfortune man console himself to find a similar case to his, who despite all the limitations of Nature nevertheless did everything within his powers to become accepted among worthy artists and men. - You, my brothers Carl and [Johann], as soon as I am dead, if Dr. Schmid is still alive, ask him in my name to describe my malady, and attach this written documentation to his account of my illness so that so far as it possible at least the world may become reconciled to me after my death. - At the same time, I declare you two to be the heirs to my small fortune (if so it can be called); divide it fairly; bear with and help each other. What injury you have done me you know was long ago forgiven. To you, brother Carl, I give special thanks for the attachment you have shown me of late. It is my wish that you may have a better and freer life than I have had. Recommend virtue to your children; it alone, not money, can make them happy. I speak from experience; this was what upheld me in time of misery. Thanks to it and to my art, I did not end my life by suicide - Farewell and love each other - I thank all my friends, particularly Prince Lichnowsky and Professor Schmid - I would like the instruments from Prince L. to be preserved by one of you, but not to be the cause of strife between you, and as soon as they can serve you a better purpose, then sell them. How happy I shall be if can still be helpful to you in my grave - so be it. - With joy I hasten towards death. - If it comes before I have had the chance to develop all my artistic capacities, it will still be coming too soon despite my harsh fate, and I should probably wish it later - yet even so I should be happy, for would it not free me from a state of endless suffering? - Come when thou wilt, I shall meet thee bravely. - Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead; I deserve this from you, for during my lifetime I was thinking of you often and of ways to make you happy - be so -

Ludwig van Beethoven

Heiglnstadt,

October 6th, 1802

Audiovisual concept

As the photographs came out of an exploration to understand the parallel (and symbiotic) relationship between a musician and the piano, I looked to sound that reflected the physicality of the instrument. The piano is an immensely complex apparatus with upwards of 12,000 parts fitted together solely for the purpose of creating 88 specific pitches. In a very geeky way, I think of the exhibitions of plastinated human bodies I’ve seen years ago in New York City — I was a bit repulsed but fascinated. This was a glimpse at the inner workings of body that few could access. Like a piano, a human body is made up of parts working together in staggering intricate system. With 78 organs, 206 bones, and an estimated 650 – 700 named muscles, the human body comes just under 1000 parts. Yet, enveloping these parts is a network of nerves, blood vessels that are impossible to put a number to. In trying to classify all the individual parts of a body, what are we hoping to find? In rummaging through the murky depths of the interior, are we hoping to come face-to-face with the soul? Would it be lounging in a bathrobe with ratty slippers, or sporting a foulard and a smoking jacket, or tossing a feather boa with satin kitten heels? Likewise, what would we find in the dark uncanny interiors of a piano where the entire chain of reactions is a complete mystery? A soul? Or a mere receptacle for the body sitting on the other side of the keyboard?

Delia’s piece, Magnus, gives a nod to the tradition of Henry Cowell and John Cage, looking to possibilities of sound that brings an awareness of the body of a piano beyond the surface of the keyboard that is traditionally the only point of contact between the musician and instrument. The quality of the soundtrack, to me, is very visceral; I think of tinnitus and other sounds within the human body. The human body is abound with sounds of activity that is normally lost to the din of environmental white noise. It has been noted that within an anechoic chamber, in absence of "white noise" that normally populates an environment, the ear becomes starved for stimulation and begins to cannibalize sounds from within the body. One’s breathing, gurgling of the stomach fluids going about its peristaltic business, the beating of the heart, become a paramount presence. Truth be told, I myself have never heard the inner workings of my body because without my aids I don’t hear anything, so I have to take the word of a hearing person’s writing.

I hope our two approaches to the piano’s physicality, one visual and one audial, comes together into a two-headed creature that may or may not be magical.

Collaboration

OLIVIA TING | concept, visual artist

olivetinge.com

oting1@gmail.com

OLIVIA TING’s fascination with moving images stems from her hearing impairment; she is deaf in one ear and has residual 22% hearing in the other. Without a hearing aid, she perceives nearly no sounds, so movements and visuals stand in for the audio that she is familiar with, but hears and not hears. Audiovisual video making and spatial projection is a way for her to understand the sounds, as a compositor who sees the grand map of how the pieces fit together. Her receipt of her cochlear implant recently has reconnected her to her classical piano background.

Formerly a pre-med science major at Pomona College, Olivia went on to a second degree in graphic design at Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles and then headed off to New York where she worked for agencies and various boutiques. But her interest in visual communication as a storytelling vehicle about the human condition brought her back to her science background, childhood training in classical piano and late start to ballet in college. Returning to San Francisco, her work has expanded to photography and video in collaboration with movement-based performers. Olivia has been nominated four times for Isadora Duncan Awards for Visual Design.

In addition to theater work, Olivia continues to work as a graphic and video media designer. Some of her clients include San Francisco Dance Center, San Francisco Performances, Brooklyn Children’s Museum and San Jose Children's Discovery Museum. She was commissioned to design a permanent exhibit video projection for part of Oakland Museum of California’s Natural History Gallery, and collaborated with architect Annette Jannotta on an San Francisco Arts Commission pilot entryway installation of their new gallery space in War Memorial Hall in San Francisco.

Olivia received her MFA degree for Art Practice from U.C. Berkeley. She is currently freelancing and developing her fine art projects.

olivetinge.com

oting1@gmail.com

OLIVIA TING’s fascination with moving images stems from her hearing impairment; she is deaf in one ear and has residual 22% hearing in the other. Without a hearing aid, she perceives nearly no sounds, so movements and visuals stand in for the audio that she is familiar with, but hears and not hears. Audiovisual video making and spatial projection is a way for her to understand the sounds, as a compositor who sees the grand map of how the pieces fit together. Her receipt of her cochlear implant recently has reconnected her to her classical piano background.

Formerly a pre-med science major at Pomona College, Olivia went on to a second degree in graphic design at Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles and then headed off to New York where she worked for agencies and various boutiques. But her interest in visual communication as a storytelling vehicle about the human condition brought her back to her science background, childhood training in classical piano and late start to ballet in college. Returning to San Francisco, her work has expanded to photography and video in collaboration with movement-based performers. Olivia has been nominated four times for Isadora Duncan Awards for Visual Design.

In addition to theater work, Olivia continues to work as a graphic and video media designer. Some of her clients include San Francisco Dance Center, San Francisco Performances, Brooklyn Children’s Museum and San Jose Children's Discovery Museum. She was commissioned to design a permanent exhibit video projection for part of Oakland Museum of California’s Natural History Gallery, and collaborated with architect Annette Jannotta on an San Francisco Arts Commission pilot entryway installation of their new gallery space in War Memorial Hall in San Francisco.

Olivia received her MFA degree for Art Practice from U.C. Berkeley. She is currently freelancing and developing her fine art projects.

Image credits

All video and color photographs by Olivia Ting

Historical illustrations are from the following sources:

Tympanic ossicles of the inner ear

Textbook of Anatomy by D.J.Cunningham, (New York, NY: William Wood and Co., 1903)

Human ear anatomy

Die Frau als Hausärztin by Anna Fischer-Dückelmann, 1911

Ribs, sternum and thoracic vertebrae

Manuel d'anatomie descriptive du corps humain by Jules Cloquet, 1825

Permanent teeth of the upper and lower jaw

Intermediate Anatomy, Physiology and Hygiene by Calvin Cutter, John Clarence Cutter, 1887

Teeth of upper and lower jaw

The Human Body and Health by Harrison G. Dyar, 1910

Production of sound by tuning fork

Industrial Encyclopedia by E.O. Laminators, 1875

Hair cells of inner ear, Organ of Corti

Dr. David Furness, Keele University, electron microscopic photograph

Hand phalange metacarpal bones Anatomie De L'Homme Ou Descriptions Et Figures Lithographiees De Toutes Les Parties Du Corps Humain by Jules Cloquet, 1825

Bones of the foot

Osteographia by William Cheselden, 1733

Historical illustrations are from the following sources:

Tympanic ossicles of the inner ear

Textbook of Anatomy by D.J.Cunningham, (New York, NY: William Wood and Co., 1903)

Human ear anatomy

Die Frau als Hausärztin by Anna Fischer-Dückelmann, 1911

Ribs, sternum and thoracic vertebrae

Manuel d'anatomie descriptive du corps humain by Jules Cloquet, 1825

Permanent teeth of the upper and lower jaw

Intermediate Anatomy, Physiology and Hygiene by Calvin Cutter, John Clarence Cutter, 1887

Teeth of upper and lower jaw

The Human Body and Health by Harrison G. Dyar, 1910

Production of sound by tuning fork

Industrial Encyclopedia by E.O. Laminators, 1875

Hair cells of inner ear, Organ of Corti

Dr. David Furness, Keele University, electron microscopic photograph

Hand phalange metacarpal bones Anatomie De L'Homme Ou Descriptions Et Figures Lithographiees De Toutes Les Parties Du Corps Humain by Jules Cloquet, 1825

Bones of the foot

Osteographia by William Cheselden, 1733

Piano model

The piano photographed (taken apart and put together and still working!) is my long-suffering 5’ 7” Model M Steinway. A lookup of the serial number on steinway.com reveals it is likely made in the year 1940.

Thanks to

for being part of this journey!

Jim Christopher

Andi Fong

Nicholas Mathew

Annamarie McCarthy

John McCarthy

Gavin Williams

Jim Christopher

Andi Fong

Nicholas Mathew

Annamarie McCarthy

John McCarthy

Gavin Williams

This activity was supported in part by the California Arts Council, a state agency,

and the National Arts and Disability Center at the University of California Los Angeles.

and the National Arts and Disability Center at the University of California Los Angeles.