Olivia Ting

photographs | (part one of two)

short film | (part two of two)

featured in Exploratorium Art+Science

AfterDark Online program 2021

1 }

Finger Soundprint

To think that one’s contact with the machinery of a piano is mainly limited to the fingertips, is an astounding understatement of the range of sounds a performer is capable of drawing from the instrument.

Just before the pandemic, I chipped the tooth off one of my keys. My piano doctor suggested a quick fix with gaffer tape, intending to return armed with glue and clamp, but then COVID happened. So the gaffer tape became the membrane between between my piano and I, a testimony of our intersection.

Just before the pandemic, I chipped the tooth off one of my keys. My piano doctor suggested a quick fix with gaffer tape, intending to return armed with glue and clamp, but then COVID happened. So the gaffer tape became the membrane between between my piano and I, a testimony of our intersection.

Finally, after a year’s worth of practice, it’s just so icky I had to retire the top layer. And so the cycle continues.

Finally, after a year’s worth of practice, it’s just so icky I had to retire the top layer. And so the cycle continues.The marks that the piano leaves on me.

2 }

Soundboard

My relationship with the piano dwindled after I lost my hearing in my right ear some 15 years ago. I couldn’t tell what sound I was making any more. I received a cochlear implant last year and it sounds very strange at the moment — being the new digital kid on the block waging a battle of wills with my brain. My brain wants to direct all hearing responsibilities to my tried and true left ear, which still holds steady at 22% residual hearing, not trusting this foreign pathway blazing like Bronco Bill into a formerly dead channel. With my CI ear, I hear a greater frequency range, but it is like trying to understand the nuances of light, dark, shades with giant flat pixels.

But come hell or high water, I will insist on using the CI, pummeling at my brain’s resistance to my deaf ear. The piano belongs to me.

But come hell or high water, I will insist on using the CI, pummeling at my brain’s resistance to my deaf ear. The piano belongs to me.

3 }

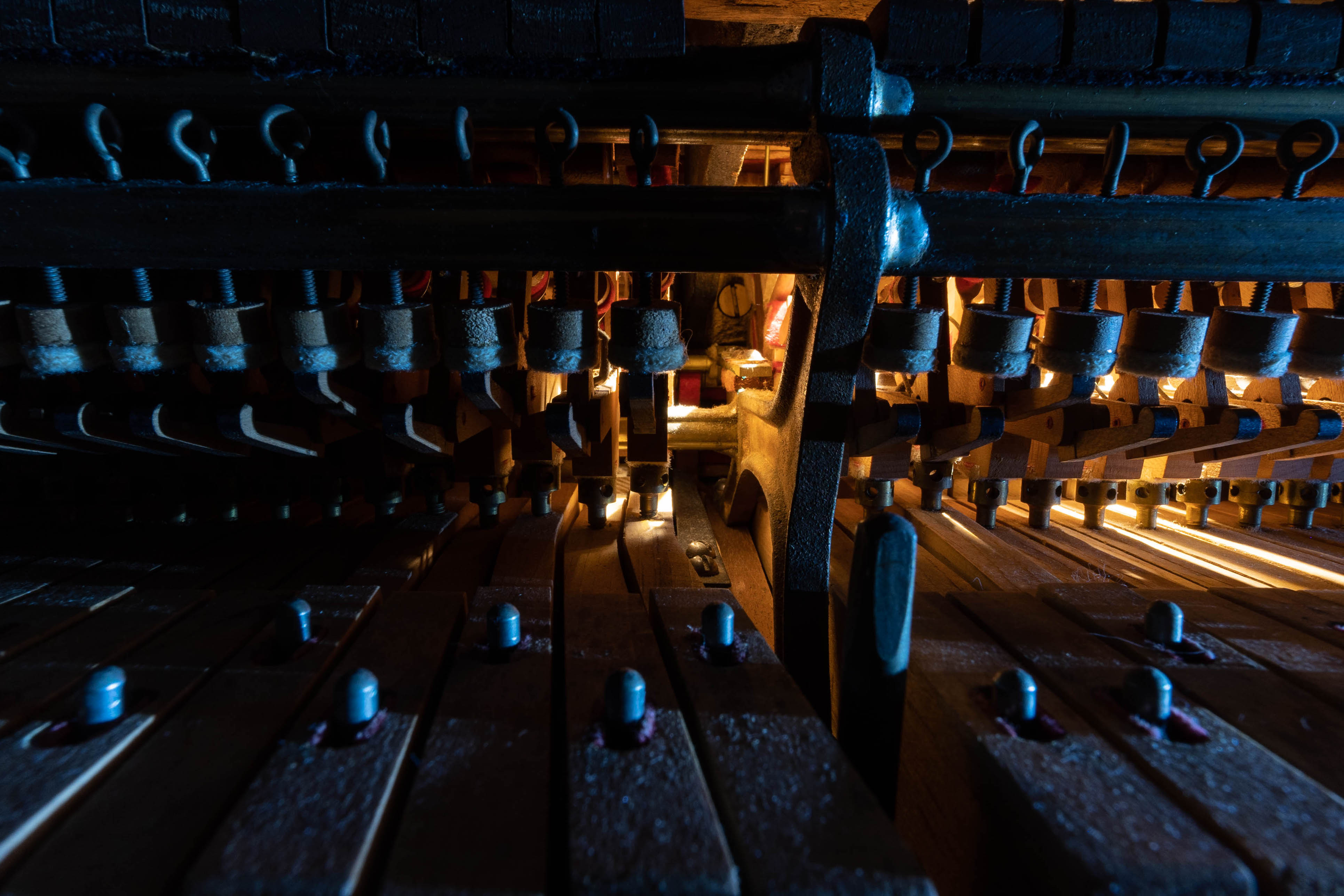

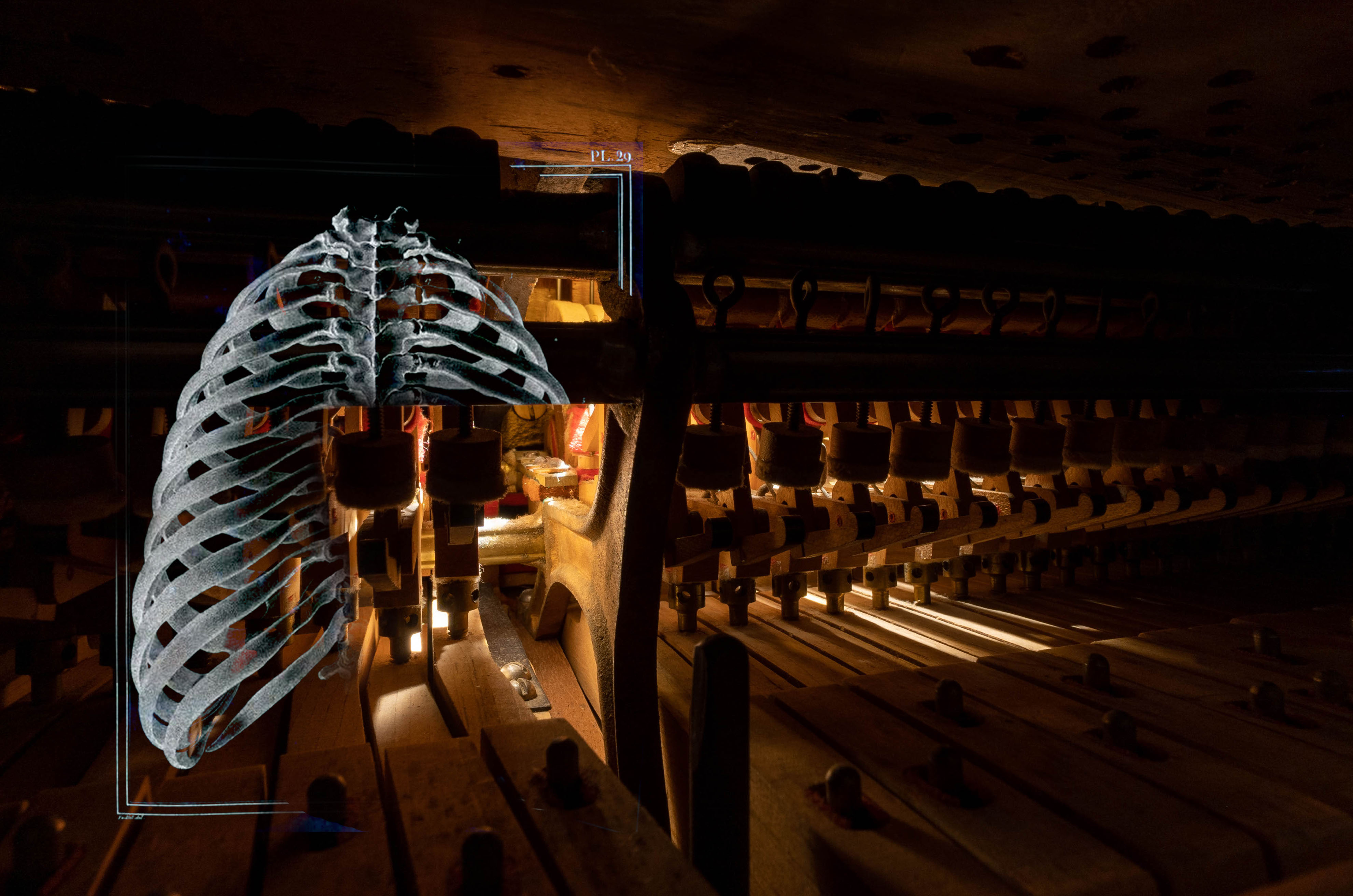

Into the Jaw of the Leviathan

Moving into the uncanny space of a piano’s sound-making interior mechanism.

A musician and a piano face each other like a looking glass — each is mute without the other. This relationship, at the most minimalist level, is a transferrence of cause and effect resulting in pulsating disturbance of air molecules that we know as sound. But what a promise of sound this complex and unseen physiology deep in the piano offers!

Probing into the cavity with my camera, perception blurs; what is tiny feels monumental, complex machinery devoted solely to the purpose of sound remains mute, pieces seem lost like marionettes with no one at the other end of the strings. Is this the vessel for... the soul of sound?

The piano’s physiology mirrors that of the performer — perhaps that is why the familiar becomes what Freud calls “unheimliche”, the uncanny, this reflection of our own bodies, physical and emotional, in the hardware of an inanimate object.

A musician and a piano face each other like a looking glass — each is mute without the other. This relationship, at the most minimalist level, is a transferrence of cause and effect resulting in pulsating disturbance of air molecules that we know as sound. But what a promise of sound this complex and unseen physiology deep in the piano offers!

Probing into the cavity with my camera, perception blurs; what is tiny feels monumental, complex machinery devoted solely to the purpose of sound remains mute, pieces seem lost like marionettes with no one at the other end of the strings. Is this the vessel for... the soul of sound?

The piano’s physiology mirrors that of the performer — perhaps that is why the familiar becomes what Freud calls “unheimliche”, the uncanny, this reflection of our own bodies, physical and emotional, in the hardware of an inanimate object.

4 }

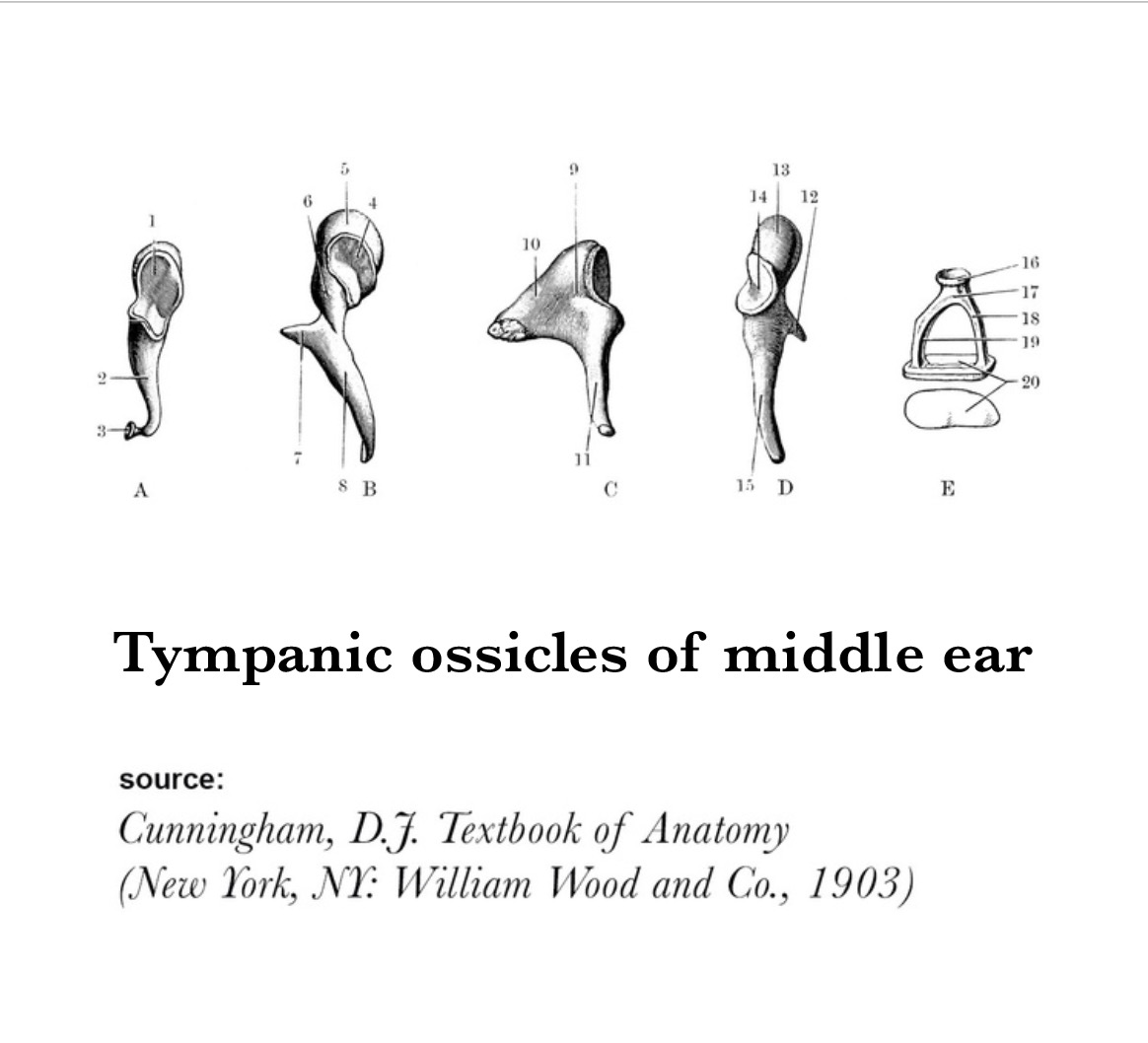

Tympanic soundcrew

The hammer against an anvil is probably one of the most enduring visual metaphor of sound — movement and impact that send shockwaves, figuratively and literally.

5 }

The beat that my heart skipped

Years ago I was struck by a film I saw by the name, “The Beat that My Heart Skipped” (De Battre Mon Coeur S'Est Arrêté) about a thuggish young man who spent his days intimidating tenants for his shady real estate gangster father. Once a classical pianist, he abandoned the piano after his concert pianist mother died. A chance encounter with his mother’s former agent, who remembered his youthful talent but unaware of his current career choices, rekindles his sidelined dream of becoming a musician.

While I was never a thug, I felt keenly the drift I had with my own relationship with the piano after my hearing dwindled. It has been nearly two years since I returned to committed practice and lessons — and it is an uphill climb, rebuilding the stamina, the technique, and above all, relearning how to own an interpretation of a piece.

While I was never a thug, I felt keenly the drift I had with my own relationship with the piano after my hearing dwindled. It has been nearly two years since I returned to committed practice and lessons — and it is an uphill climb, rebuilding the stamina, the technique, and above all, relearning how to own an interpretation of a piece.

6}

Song without sound

When a tree falls in a forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

This philosophical question has been pondered since the 1700s, but I would like to rephrase it as: “if no one is there to see it, does it make a sound?” One morning earlier than usual, I put on my hearing aids upon waking, as is my usual ritual. Unbeknownst to me, I had forgotten to turn them on, so I was hearing virtually nothing, except for very faint bumps of low noise. I just thought I was extraordinarily...quiet. I was rather pleased, envisioning myself as a shadow slicing through the still darkness of dawn while the rest of the house is still asleep. I started making my breakfast, serene in my pool of light emanating from above the stove.

Imagine my shock when the kitchen light flipped itself on. I turned to see my irritated pajama-ed household squinting at me with their mouths moving; but no voices emanated.

I fiddled with my hearing aid —and my smug quietude exploded with a rattling of akin to demons thrashing in Pandora’s Box. Evidently, when turning on the stove overhead light, I hit the wrong button and inadvertantly turned on the range hood as well. I had been hypervigilant for any potential friction of objects that could make any sort of noise, but a tiny button in the dark escaped me.

So much for my imagining myself a ninja.

This philosophical question has been pondered since the 1700s, but I would like to rephrase it as: “if no one is there to see it, does it make a sound?” One morning earlier than usual, I put on my hearing aids upon waking, as is my usual ritual. Unbeknownst to me, I had forgotten to turn them on, so I was hearing virtually nothing, except for very faint bumps of low noise. I just thought I was extraordinarily...quiet. I was rather pleased, envisioning myself as a shadow slicing through the still darkness of dawn while the rest of the house is still asleep. I started making my breakfast, serene in my pool of light emanating from above the stove.

Imagine my shock when the kitchen light flipped itself on. I turned to see my irritated pajama-ed household squinting at me with their mouths moving; but no voices emanated.

I fiddled with my hearing aid —and my smug quietude exploded with a rattling of akin to demons thrashing in Pandora’s Box. Evidently, when turning on the stove overhead light, I hit the wrong button and inadvertantly turned on the range hood as well. I had been hypervigilant for any potential friction of objects that could make any sort of noise, but a tiny button in the dark escaped me.

So much for my imagining myself a ninja.

7 }

Articulation

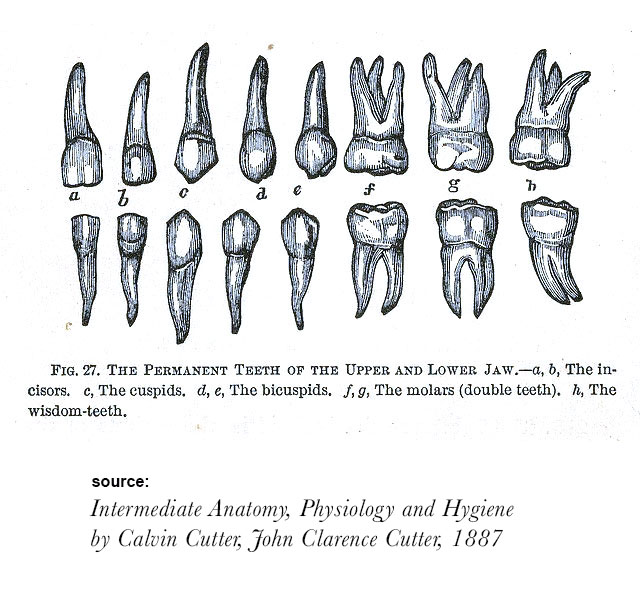

I used to have speech therapy classes in third grade, which I hated. I was in denial that I spoke differently from anyone else; I had no idea what I was not doing. Simply put, I was not enuciating sounds that I wasn’t hearing. I had no reference for arranging my tongue position in the cavity of my mouth to create these sounds that are supposedly there, but just not to me. Not only were these sounds inaudible, they were also invisible.

Articulation on the piano, by contrast, was(is) an achievable set of exercise — I could see and feel the enunciation of each note by the technique employed: legato, staccato, pedal, octaves, argeggios, etc.

Articulation on the piano, by contrast, was(is) an achievable set of exercise — I could see and feel the enunciation of each note by the technique employed: legato, staccato, pedal, octaves, argeggios, etc.

8 }

Inner hearing/

pitch perfect

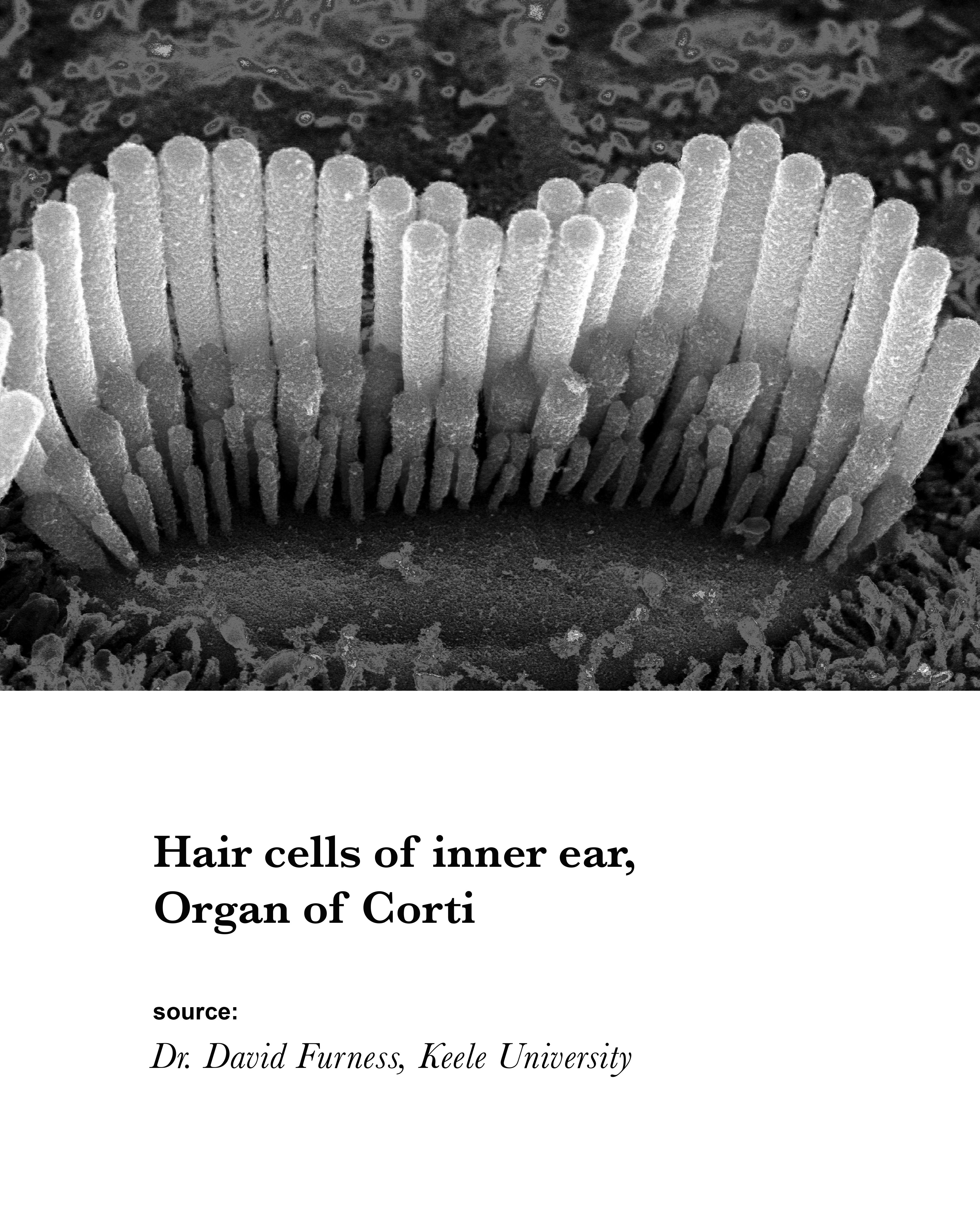

To think of the uncanny parallel between the forms of a forest of tuning pins on a piano and the microscopic hair cells hidden deep within the human inner ear is to beg the question of the chicken or the egg. One would be tempted to think of biomimicry here, but in this case, pianos and their predecessors were recorded to have been made as far back as the 1400s, when no technology existed for anyone to know the physiology of the inner ear, let alone hair cells.

9 }

Reverberations

When I started photographing the interior of my piano I was struck by how architectural it is. I have shifted the configuration of the moving. parts in order to fit a camera in; the chain of reaction connectivity has been broken.

This exercise of witnessing a space that is accessible to few meant silencing the mechanics of a space intended for sounds. In the muteness the viscera bear all the more powerful testimony to the promise of music they are capable of delivering, like a breath arrested.

This exercise of witnessing a space that is accessible to few meant silencing the mechanics of a space intended for sounds. In the muteness the viscera bear all the more powerful testimony to the promise of music they are capable of delivering, like a breath arrested.

10 }

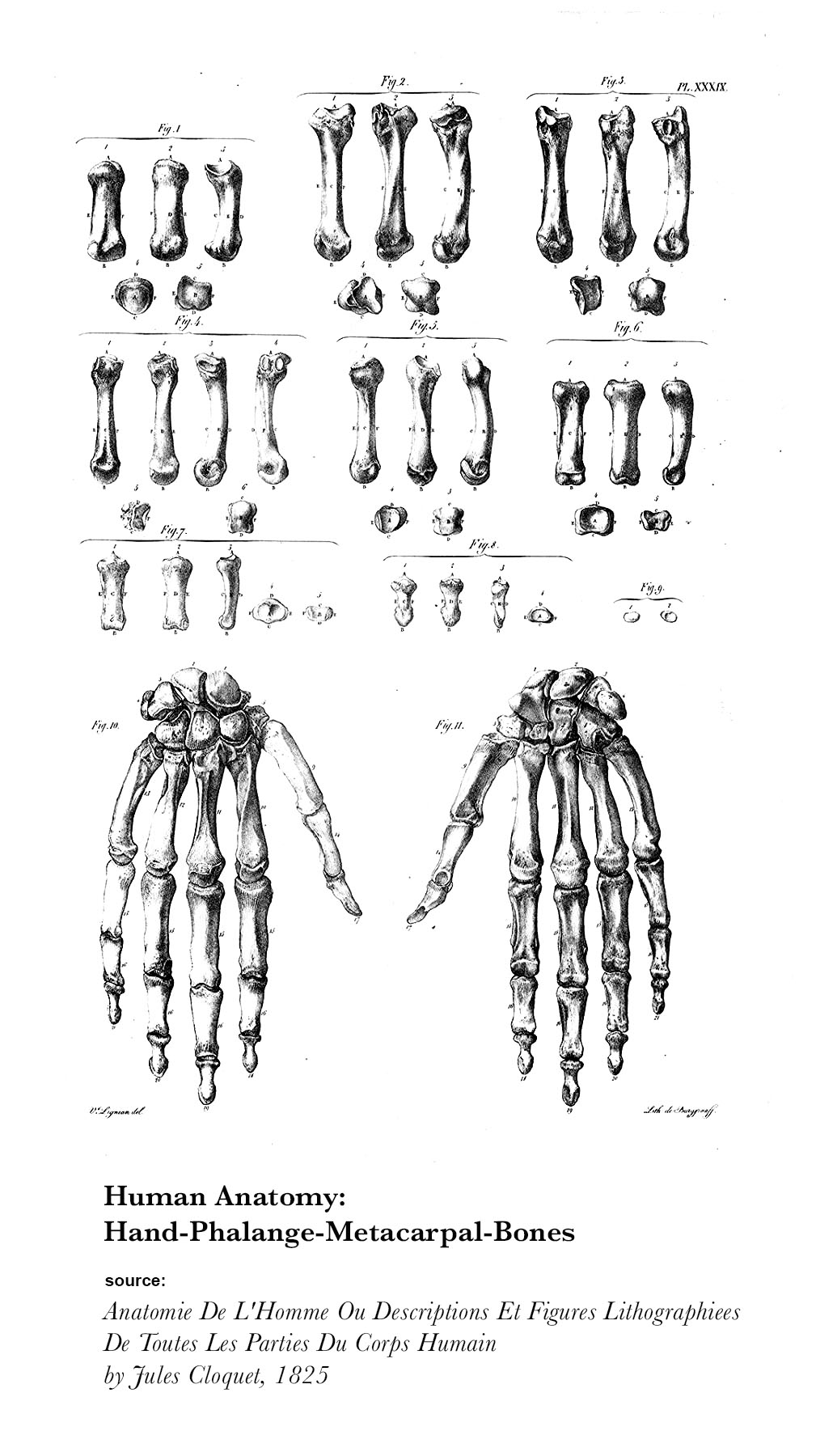

Metacarpals

11 }

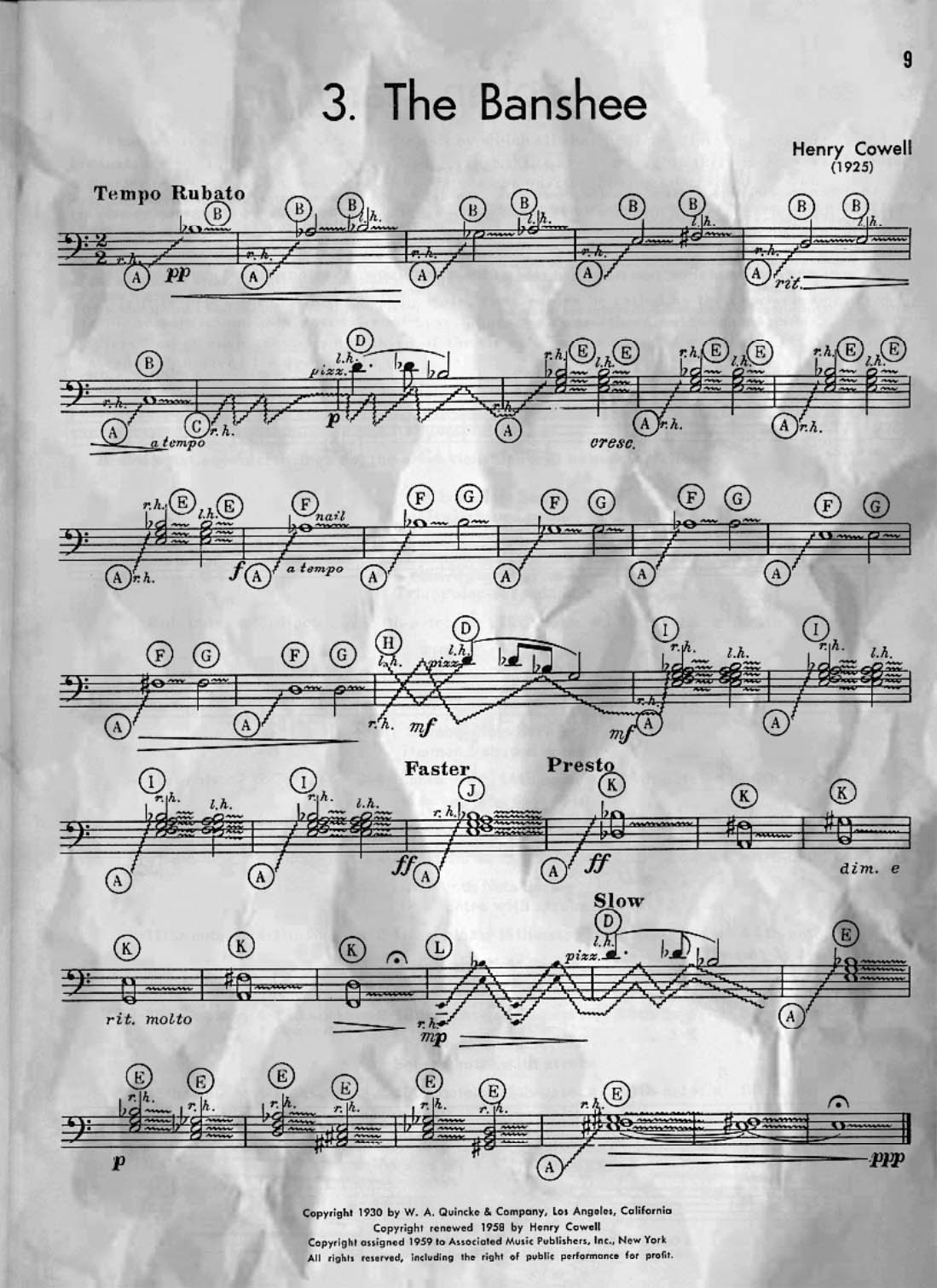

The Banshee

The Banshee was the first piano piece (composed by Henry Cowell, 1925) to be performed completely without the use of the keyboard. The performer plays the piece with his/her hands in direct contact on the strings on the soundboards, viscerally conjuring the spirit of the banshees by running fingers through their hair.

12 }

Metatarsals

short film | (part two of two)